Introduction

Studies of pictorial behavior in chimpanzees suggest that drawing and painting are self-motivated behaviors that can be used as a form of enrichment.44 While previous studies have established credible links in visual preference between macaques and humans,45 very few studies have engaged with the picture making behavior of macaques.

This is partially due to logistics. While chimpanzees are documented tool-users and can be trained to use a brush or pencil, macaques do not tend to use tools in the wild and have difficulty mastering this skill.46 As a result, rhesus macaques have been limited in the past to finger painting, a technique that some experts have rejected as inadequate for analysis due to the difficulty of interpreting any individual markings.47 Using the iPad we can circumvent these challenges. No tool-use is required, and the multiple contacts of a macaques’ fingers are translated into a single stroke, aiding clarity of analysis.

At present there are two competing hypotheses to explain the motivation of primate pictorial behavior. The first, advanced by Desmond Morris, is that primates engage in drawing and painting to create a sense of order and balance in the pictorial field. An alternative, proposed by aesthetician Thierry Lenain, is that this picture-making behavior functions as a form of disruptive play.

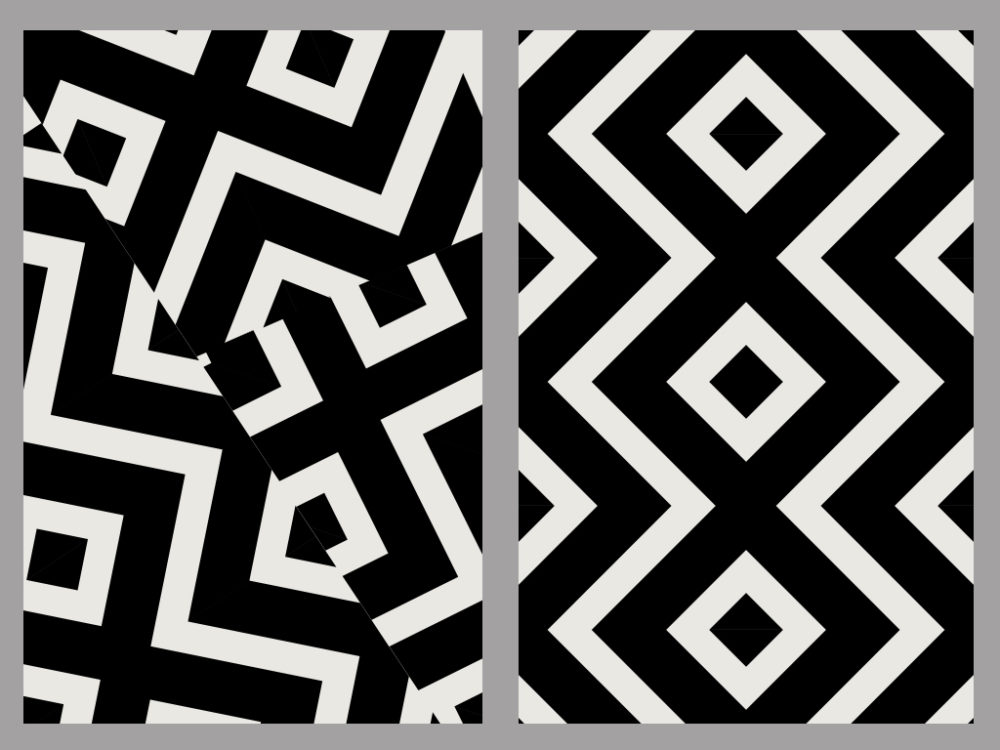

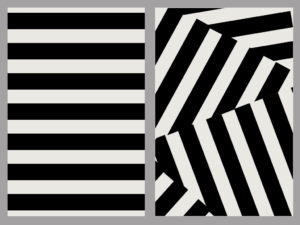

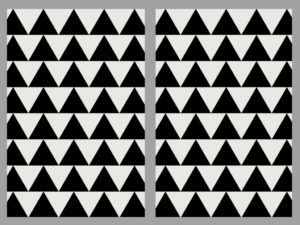

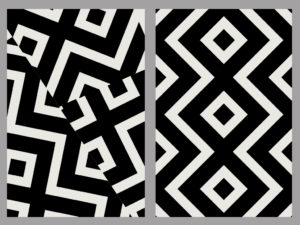

We investigated whether the pictorial behavior of adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) could be characterized as disruptive or ordered. A series of patterns were introduced to the macaques, presented side by side on the iPad: on one side, a symmetrical pattern, on the other, asymmetrical. To control for left and right side preference, the side each pattern appeared on was alternated, and fully symmetrical control images were included. Additionally, the amount of black and white space present in each pattern was controlled for.

Experimental pattern with right side asymmetry.

Experimental pattern with complete symmetry.

Experimental pattern with left side asymmetry.

If primates are attempting to disrupt the pictorial plane, we can expect them to be more likely to draw on the symmetrical side of the experimental image. On the other hand, if they are responding to order, they will be more likely to draw on the asymmetrical portion of the composition to bring it in line with the symmetrical version.

Materials and Methods

Four adult rhesus macaques (two female), pair housed, were given access to the iPad across 10 sessions, during which multiple trials were run. During each trial, the macaques were presented with the iPad running the commercially available application Procreate™, and displaying one of the experimental pattern images. Each iPad was housed in a Lifeproof™ FRĒ waterproof case, which in turn was enclosed in a high density polyethylene case, and clamped to a cart or the foraging board on the home cage. The macaques were then allowed to interact with the image: any mark made on the image is visible as a red stroke. A trial was considered complete when the monkey stood and moved away, or demonstrated behaviors unrelated to the activity: self grooming, for instance. The experimenter then removed the iPad and either presented a new image or ended the session.

The resulting digital images were then transferred to a computer for analysis in Adobe Photoshop™. By selecting the red color range, and running that data through the program’s Histogram, we determined the number of pixels present in the strokes on either side of the experimental image, which are then recorded as a percentage. The percent coverage of each half of the composition can then be compared to determine preference for drawing on the symmetrical or asymmetrical pattern.

Results and Discussion

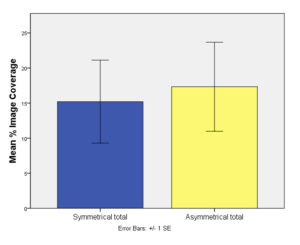

Using a paired t-test, we determined there was no significant difference in percent image coverage of asymmetrical versus symmetrical patterns (t(3)= -1.060, p>0.1).

Percent image coverage does not vary significantly between symmetrical and asymmetrical images.

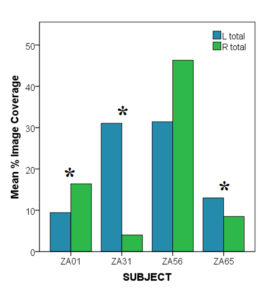

However, we did find a significant side bias in 3 of 4 subjects. To measure side bias, we created a side bias index (SBI) by modifying the handedness index (HI) established by Hopkins.48 Using the formula [SBI=(R − L) / (R + L)] with positive values reflecting right side bias and negative values reflecting left side bias, and values over .20/-.20 indicating significance, we found that 2 subjects had a significant left SBI, and 1 subject had a significant right SBI. The subject that did not demonstrate a significant side bias scored a marginal .19, trending toward right side bias.

Percent image coverage shows side bias in multiple subjects.

There are several possible explanations for these results. The patterns may not be perceived as a relevant stimulus by the macaques. Additionally, the side bias may be confounding any preference for symmetry or asymmetry that the subjects may have. However, there is some evidence that, regardless of the outcome of the experiment, interaction with iPad is an effective form of enrichment. The subjects voluntarily interacted with the iPad without reinforcement, indicating that the activity is intrinsically rewarding.

44 Morris, p. 158.

45 Steckenfinger, p. 18362-18366.

46 With some notable exceptions: See Veino, C.M. and Melinda Novak. “Tool us in juvenile rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)” The Twenty-sixth ASP Meeting Calgary, Alberta, Canada, July 30-August 2, 2003. Calgary: American Society of Primatologists, 2003. Web.

47 Morris, p. 26.

48 Hopkins, William D. “Independence of Data Points in the Measurement of Hand Preferences in Primates: Statistical Problem or Urban Myth?” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 151(1), 2013 May. 151-157. Web. 8 April 2016.